Identifying high-potential employees

How can high-potential staff be identified? Part of the answer lies in the personal characteristics to be taken into consideration. Like in the debate on definitions, there is no real consensus as to the personal characteristics to be considered when seeking to identify high potential. In reality, there are very few models that focus on the question and even fewer generic models, given the fact that it is crucial to first look at the subject of the potential. In fact, most models are developed by consultancies and have not been scientifically studied (Silzer & Church, 2009). However, Silzer & Church (2009) undertook a conceptual analysis of the concept of potential based on a dozen models published and presented during professional encounters. They defined three dimensions to which they assigned each of the various personal characteristics to be considered when identifying high potential: foundational dimensions, growth dimensions and career dimensions.

Foundational dimensions

Foundational dimensions are constant and stable; they are relatively unlikely to develop further or to change across situations, time or experiences (Silzer & Church, 2009). Cognitive style (such as conceptual and strategic thought, cognitive ability and ability to handle complex, ambiguous situations) and personality (e.g. sociability, interpersonal skills, dominance, emotional stability and resilience) are both foundational dimensions.

Growth dimensions

Growth dimensions are those that facilitate or hinder growth and development in other domains. They are relatively stable from one situation to the next, but improve when an individual is working in an environment where he/she is supported and encouraged, and when he/she has a strong interest in a particular domain and has the opportunity to learn more about his/her fields of interest (Silzer & Church, 2009; Morin, 2010). Learning skills (e.g. adaptability, learning orientation and openness to comments and feedback) and motivation (such as energy and career ambition) are two such dimensions.

Career dimensions

Career dimensions are the best indicators of future professional competencies. These aspects include current performance (e.g. performance record and work experience), knowledge (e.g. technical and functional knowledge and competencies), values (such as compatibility of personal values with those of the organization, and values and norms appropriate to career path), as well as managerial qualities (capacity for change management, developing and managing people, exerting a positive influence on others, constructive criticism of the established order, etc.).

Although the Silzer & Church model (2009) provides a practical summary of the existing literature on potential, a number of questions remain unanswered: Does an individual have to have all the characteristics and dimensions presented in order to qualify as “high-potential”? Are some dimensions more vital than others? It would appear that the foundational and growth dimensions are rather universal components of potential (Silzer & Church, 2009). In other words, all high-potential individuals should display these characteristics. However, not all talented employees will exhibit the career-related aspects, which will depend more heavily on the different potential pools (Silzer & Church, 2009). In short, as was previously mentioned, it is important to identify the subject of the potential before it will be possible to determine the relevance of these different aspects in identifying an organization’s “A players.”

Among all the characteristics and aspects raised, no one of these on its own is sufficient to identify an individual as “high-potential.” However, a number of organizations use a single source of information to predict an individual’s future success: past performance (Robinson, Fetters, Riester & Bracco, 2009). These organizations make the mistake of confusing employee performance with employee potential. Managers need to avoid falling into the trap of the performance-potential paradox (Morin, 2010; Mone, Acritani & Eisinger, 2009). While an employee’s current productivity is a valuable indicator, it is not enough for a real analysis of that individual’s potential (Robinson et al., 2009). Yet an examination of employees’ past behaviours is necessary when evaluating their talent. By past behaviours, we mean that an individual should be observed over an extended period of time, in a multitude of situations associated with his/her work (Morin, 2010; Robinson et al., 2009). In short, identifying potential is not based on a single shining achievement. The next section sets out an approach to identifying talented employees while avoiding the performance-potential paradox.

Suggested steps to identifying high-potential employees

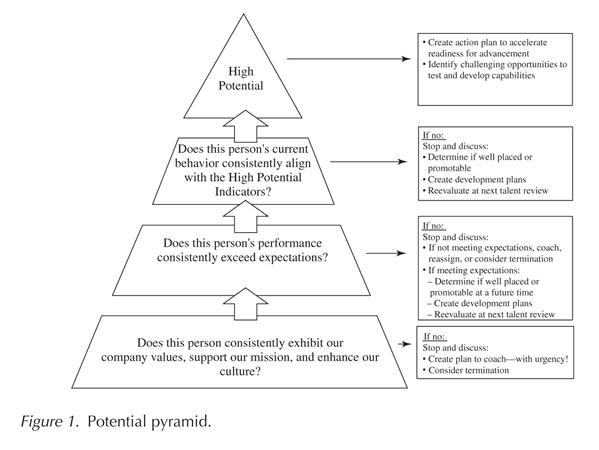

Robinson et al. (2009) continued the examination begun by Silzer & Church (2009). They have provided a model to help managers to direct conversations and to make decisions that look beyond employee productivity. More specifically, they developed a “potential pyramid” (Robinson et al., 2009). This pyramid provides structure to the decision-making process. Following this logic, managers ask the same questions when assessing each of their staff members. If an employee meets or exceeds the criteria for a given step, he/she moves on to the next one. Where an employee does not satisfy a step’s requirements, suggestions are made to help him/her improve in that area.

The Robinson et al. (2009) potential pyramid

Step 1: Company mission, values and culture

The base of the pyramid represents the organization’s underlying mission, along with its values and culture. This stage involves an assessment of whether or not the employee’s behaviour reflects these points (Robinson et al., 2009). Alignment between individual and corporate values and culture is becoming more and more important in the business world, in which talented individuals must portray the company’s values and contribute to its culture (Garrow & Hirsh, 2008; Ostroff & Judge, 2007).

Step 2: Performance

The second step consists in assessing the employee’s performance in his/her current role, as well as in past positions. At this point, the manager needs to consider: (a) whether the employee constantly exceeds expectations and his/her obligations to the organization; (b) whether the employee supports his/her colleagues; (c) whether the employee has the support of his/her peers; and (d) whether the employee has a positive influence on other members of the organization. A candidate who meets these criteria “moves up” to the next step.

Step 3: High potential indicators

This step involves an evaluation of the individual based on several additional indicators of high-potential employees (Robinson et al., 2009). Basically, it is at this point that high-potential pools (potential for what?) stand out. In other words, the characteristics selected for a particular pool will differ from one to the next, even within the organization (Silzer & Church, 2009). For example, for a talent pool used to fill general and upper management positions, the criteria at this stage will be competencies like the ability to rally and lead, political awareness and strategic vision, whereas the criteria for a research and development pool will focus more on innovation (Graen, 2009; Henson, 2009).

Step 4: High-potential employees

Individuals with a positive assessment at all the previous steps are considered high-potential employees (Robinson et al., 2009). Thus, the fourth and final step entails the creation of an action plan for these team members in order to foster their advancement and to provide them with opportunities to further develop their skill sets (Robinson et al., 2009).

The model developed by Robinson et al. (2009) is a practical one, as it reduces the risk of assessing employees based on snap judgements and first impressions. By systematically applying this process to all staff, it also becomes easier to screen for talent among employees whose personality is not as strong and who are naturally more reserved (Morin, 2010). In addition, the model is consistent with suggestions in the literature in the field. Indeed, the talent management approach recommends that employees be informed of how they have scored and provided with suggestions for improvement, so that everyone at the organization can learn and grow (Dominick & Gabriel, 2009; Yost & Chang, 2009). Thus, by emphasizing that potential is not set in stone and that it is re-assessed from time to time, the company can reduce the risk of demoralizing employees not perceived as talented (Mone et al., 2009). This means that it is within the power of “C players” to become “B players” and “B players” to become “A players” (Yost & Chang, 2009). Finally, another strength of this model is that it offers a common basis for all managers and supervisors to use to identify high-potential employees (Heslin, 2009). Shared understanding is the foundation of any effective talent management system (Silzer & Church, 2009).

The fourth and final article in this series will suggest subjects for further consideration in terms of the talent management approach and the models provided in the first three articles.

Philippe Longpré, PhD Cdt.

Marilyne Pigeon, PhD Cdt.

References

Dominick, P.G. & Gabriel, A.S. (2009). “Two sides to the story: an interactionist perspective on identifying potential.”Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 430-433.

Garrow, V. & Hirsh, W. (2008). “Talent management: issues of focus and fit.” Public Personnel Management 4, 389-402.

Graen, G. (2009). “Early identification of future executives: a functional approach.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 437-441.

Heslin, P.A. (2009). “‘Potential’ in the eye of the beholder: the role of managers who spot rising stars.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2.

Henson, R.M. (2009). “Key practices in identifying and developing potential.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 416-419.

Mone, E.M., Acritani, K. & Eisinger, C. (2009). “Take it to the roundtable.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 425-429.

Morin, D. (2010). “Rendement et potentiel élevés : essentiels à la gestion des talents.” Atwww.portailrh.org/effectif/fiche.aspx?p=403222.

Ostroff, C. & Judge, T.A. (2007). Perspectives on Organizational Fit. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Robinson, C., Fetters, R., Riester, D. & Bracco, A. (2009). “The paradox of potential: A suggestion for guiding talent management discussions in organizations.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 413-415.

Silzer, R. & Church, A.H. (2009). “The pearls and perils of identifying potential.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 377-412.

Yost, P.R. & Chang, G. (2009). “Everyone is equal, but some are more equal than others.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2, 442-445.