Knowledge retention… How can you ensure it?

If you were asked to identify the most important assets for an organization, which items would be at the top of the list? Let’s do the exercise! Before you go any further, take a moment to think about it.

And? In reality, considering that no organizational practice can function (at least effectively) without knowledge – it makes sense to put it at the top of the list. Do you remember them? Let us first see how their essential nature is expressed in the context of the workplace – you’ll be the judge!

Organizational knowledge

In fact, knowledge itself transcends information and is understood as the potentiality to act on information (which is data): it is an instrument in relation to which we attribute meanings to the objects/subjects that surround us in an organization (Pyrko et al., 2017). These meanings, in turn, help us to act. When an individual uses his or her knowledge in the exercise of his or her practice, this is called know-how; so-called practical skills. In organizations, knowledge is what allows us to create products or services, and it is a competence that allows us to mobilize or operationalize this knowledge (Dosi et al., 2008). In this sense, individual knowledge constitutes know-how integrated into the activities of any organization and is a competitive asset whose value is inestimable in an economy such as ours, i.e. a knowledge economy (Chartrand-Beauregard et al., 2005; LaFayette et al., 2019; Laroche, 2002; Rezny et al., 2019).

Protecting organizational knowledge

As knowledge is essential for profitability, growth, and the survival of organizations, it is also imperative to put strategies in place to ensure the retention of organizational knowledge. Indeed, the continuity of organizational knowledge is constantly under threat: staff turnover, deployments, recourse to external resources, resistance to learning, technological interruptions or any unexpected departures are factors that can lead to a loss of organizational knowledge (Levallet and Chan, 2019). To counteract these adverse events, it is important for organizations to protect their organizational knowledge.

But what is organizational knowledge retention and why is it (IF) influential to address it? Retention occurs when the knowledge of an organizational actor has been transferred to the organization and can therefore be used again in the future, even if the original holder leaves the organization. Otherwise, the consequences resulting from the intra- and inter-mobility of experts – i.e. employees with significant experience and knowledge of the organization can be significant for organizations. In particular, the loss of organizational knowledge can be extremely costly for an organization and lead to a decrease in productive capacity, credibility with customers and customer satisfaction. This can lead to a decrease in profitability and morale for some employees.

In the work environment, organizations are vulnerable to their environment. This vulnerability is mainly linked to their ability to obtain and retain the resources they need to operate effectively. These include, of course, human capital, but also, and equally importantly, knowledge (Rouleau, 2007). To some extent, an organization’s ability to retain its resources depends on the environmental factors it faces (economic, socio-political, etc.). Among other things, these factors may or may not be constraining, and the organization’s ability to control its resources will determine its environment’s constraining nature (Rouleau, 2007). Therefore, it is up to managers to ensure that they have the means to reduce their organization’s dependence on the environment by ensuring the retention of its resources internally. This is particularly true for the knowledge that is the source of their practice. Based on the study by Canadian authors Levallet and Chan (2019), we propose solutions to ensure the retention of organizational knowledge, while minimizing the risks of disruption.

How do you retain them?

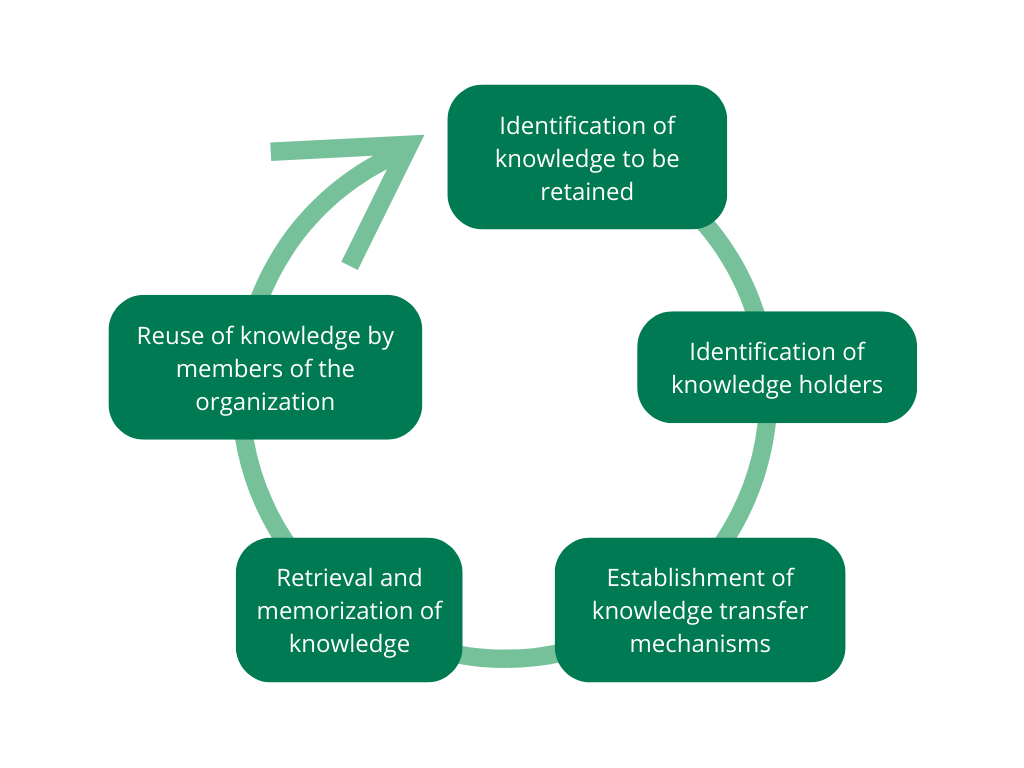

Obviously, all methods related to observation, participation, focus groups and post-mortem practices (lessons learned, etc.) are strategies that can support knowledge retention in organizations. Increasingly, information technology (IT) is seen as a catalyst for knowledge retention (Levallet and Chan, 2019). These methods and technologies are therefore knowledge transfer mechanisms (KTMs), i.e. channels through which knowledge can be retained and reused. The objective of a knowledge transfer mechanism is therefore to ensure knowledge retention in an organization. Moreover, knowledge retention is a cycle – a process that must be continuously maintained within organizations. In line with the literature on knowledge management (De Long and Fahey, 2000), we propose to illustrate the knowledge retention cycle, and therefore the key stages that constitute it, in the figure below.

Thus, having first identified the important knowledge to be retained and then its owner, it becomes important to mobilize the appropriate mechanisms for its transfer. Although knowledge management systems are known to improve organizational and individual performance, it is important to choose them carefully. To determine which mechanism is best suited to your needs, you must first recognize the type of knowledge to be retained. Consequently, we propose below a typology of knowledge related to the world of work, and then propose the retention mechanisms that are best suited to it. Taken from Levallet and Chan (2019), the typology suggests two main categories of knowledge, namely explicit, which refers to objective, technical and logical knowledge that is easily codifiable and therefore transferable, and implicit, i.e. more subjective knowledge derived from experience and which, as it cannot be easily transcribed or codified, is more difficult to transfer.

Under each of these two main categories, there are two levels of knowledge, namely individual and collective (social). Let us see how knowledge is articulated under each of these sub-categories, and what are the appropriate transfer mechanisms for each.

Explicit knowledge (objective, logical, technical – easily transferable)

Individual level: conscious knowledge

- Explicit individual experiences and knowledge

- Appropriate transfer mechanisms: notes, paper files, digital files, e-mail box, Excel workbooks, individual database, etc.

Social level: objective knowledge

- Collective knowledge that can be captured and codified

- Appropriate transfer mechanisms: organizational databases, repositories, guides and procedures, training, shared folders (sharedrive style, wikis), etc.

Implicit knowledge (subjective, cognitive – not easily transferable)

Individual level: automaticknowledge

- Latent or implicit individual knowledge and habits

- Appropriate transfer mechanisms: one-on-one activities, direct observation, mentoring, individual discussions, individual training, preservation of e-mails, etc.

Social level: collective knowledge

- Cultural knowledge, implicit and embedded in social norms

- Appropriate transfer mechanisms: informal discussions and meetings, teamwork, working committees, company social platform (Yammer style, Teams), company website and social networks, etc.

Of course, while some mechanisms have been grouped under specific categories of knowledge, they can also support the retention of other types of knowledge. For example, observation is a strategy for retaining both explicit and implicit knowledge and is therefore not specific to the latter category. Finally, the proposed typology is not exhaustive, and some mechanisms are more effective in certain contexts: your job is to know how to identify them well, depending on the retention needs of your organization.

In conclusion, organizational knowledge is fundamentally human made. It is through interaction with each other that organizational knowledge is developed. In recent years, many organizations have found themselves lacking knowledge, and have therefore experienced significant disruption caused by their environment and their inability to retain the resources necessary to deal with it. This economic transformation of knowledge and learning only serves to highlight the centrality of talent as a competitive advantage in an environment of innovation and change.

And then, is the retention of organizational knowledge important or not?

References

Chartrand-Beauregard, J., Gingras, S. et Hébert, G. (2005). L’économie du savoir au Québec. Québec : Ministère du développement économique, de l’innovation et de l’exportation, Direction de l’analyse économique et des projets spéciaux.

De Long, D. W. et Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 113-127.

Dosi, G., Faillo, M. et Marengo, L. (2008). Organizational Capabilities, Patterns of Knowledge Accumulation and Governance Structures in Business Firms: An Introduction. Organization Studies, 29(8-9), 1165-1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840608094775

LaFayette, B., Curtis, W. C., Bedford, D. A. D. et Iyer, S. (2019). Knowledge economies and knowledge work. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Laroche, G. (2002). Économie du savoir : mythe ou réalité? Dans C. d. e. t. s. l. e. e. l. technologie (dir.). Montréal : CETECH, Direction de la planification et de l’information sur le marché du travail.

Levallet, N. et Chan, Y. E. (2019). Organizational knowledge retention and knowledge loss. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(1), 176-199. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-08-2017-0358

Pyrko, I., Dorfler, V. et Eden, C. (2017, Apr). Thinking together: What makes Communities of Practice work? Hum Relat, 70(4), 389-409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716661040

Rezny, L., White, J. B. et Maresova, P. (2019). The knowledge economy: Key to sustainable development? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 51, 291-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2019.02.003

Rouleau, L. (2007). Théories des organisations. Presses de l’Université du Québec.